Haptic, Tactile, Sensory, Motor: Crucial to #DeeperLearning

My friend Terry recently wrote about using his mind as a “fulcrum” and physical writing instruments as “levers” for analyzing and annotating (physical) texts. This led to a whole flurry of responses, with many wistfully recalling the “old days” of writing in books, doodling, scrapbooking, etc. There was a unanimous yearning to return to some of those old habits.

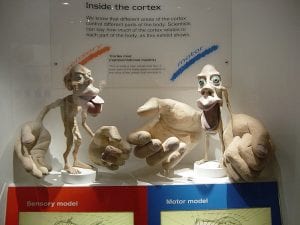

This discussion led me to explore (again) the evidence that haptic feedback is a vital, integral part of being human. I first thought of the sensory and motor homunculi, grotesque-looking representations first created by Dr Wilder Penfield in 1937 that illustrate the quantity of grey matter devoted to various body parts. The hands take up a highly disproportionate amount of space, suggesting we are meant to use our hands often and well.

Sensory and motor homunculi by Dr. Joe Kiff shared under a [CC BY-SA 3.0] license.

Smashing Design, an online magazine for web designers and developers, argues in Designing for the Tactile Experience that new and evolving technologies must be mindful of incorporating tactile and motor interactions. Several times, the author emphasizes that meaning is found in our experience of the world, not only in how we act in it, but how it acts upon us. If we are not physically interacting with the world, our experience is being very limited.

In 2016, NPR reported on a 2014 study that showed college students taking lecture notes by hand did better on “concept-application” tests, wherein they were required to apply the lecture information to an open-ended question.The difference in results held true even when the students were given time to review their notes between the time of the lecture and the test.

The need for a tactile relationship to #deeperlearning applies even (more?) at young ages. A 2012 study of preliterate five-year-olds tested the recall of children who were assigned to one of typing, tracing, or printing letters and shapes. fMRI scans showed that a letter recall task recruited the “reading circuit” area of the brain only in the children who had handwritten the letter.

There is a growing recognition within K-12 education that “making” is not only fun, it also aids learning. In addition to the general trend toward “makerspaces” in schools and communities, Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education has a Project Zero initiative underway called Agency by Design, which is “investigating the promises, practices, and pedagogies of maker-centered learning experiences.”

I say a hearty amen to Terry’s “Theoria (thinking), Poiesis (making), & Praxis (Doing).”