We are wrapping up the first formal week of #CLMOOC 2017, where we were optionally (after all, everything in CLMOOC is optional) invited to add an introduction in Flipgrid. Flipgrid is a video-only platform, and my CLMOOC colleagues have used a variety of methods to introduce themselves; some funny, some serious, some silent.

I had the idea to create a video that emulates an old-style flip book, so went searching for a tool to use. I found FlipAnim, which seemed quite straightforward, a web-based app which had a short learning curve. The first (disappointing) thing I discovered is there is no “erase” or “undo” capability. The only way to remove mistakes is by deleting the whole “page.” The second “problem” with this tool is that the drawing is done using one’s computer mouse.

Even though I am left-handed, I have always used a right-handed mouse (maybe for the same reason I still use right-handed scissors – lack of availability when I first started using the tool?). When I was faced with the prospect of applying my atrocious right-handed drawing-with-a-mouse skills, along with the can’t-undo-mistakes reality, I sighed and considered finding a different app.

Then I thought better of it, and simply drew. I accepted that the result would be “primitive” at best. And discovered it was so liberating to play! I was relaxed and reckless as I created my crude facsimile of a girl with wild hair, and as I hand-wrote, er mouse-wrote my “credits.” Yes, the result is primitive, but it was such fun!

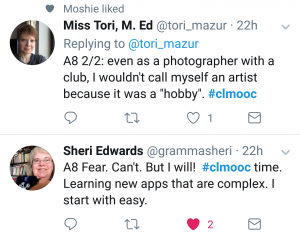

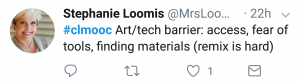

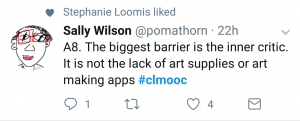

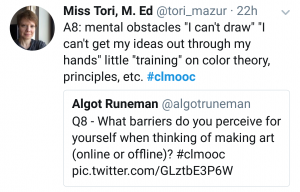

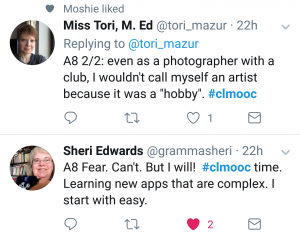

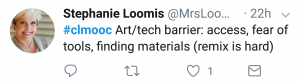

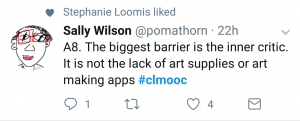

This experience ties in with the Twitter chats we had a few days ago, where a number of us acknowledged we feel we aren’t artists, that we are “bad” at art.

Our perception that we are not “artists” usually starts at a young age, oftentimes as the result of a classroom experience. My absolute favorite example of using a positive, iterative process to improve work comes in the form of “Austin’s Butterfly,” from Expeditionary Learning’s Ron Berger. In this process, instead of telling students their work is “bad” or “good,” peers offer “kind, specific and helpful” feedback. If you haven’t watched this video, DO! It provides such a superb example of how first-grader Austin steadily improves his work based on peer feedback, and how closely his final product resembles the photograph he was using as his model.

Confidence in the ability to continuously improve one’s work is a characteristic identified in Carol Dweck’s research on growth mindsets. It is interesting that many of us who participated in the CLMOOC Twitter chats demonstrated a fixed mindset regarding our artistic ability.

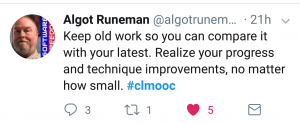

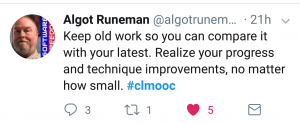

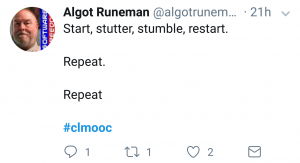

As we explored this discomfort and feelings of inadequacy further, we talked about the need to “play” with art, to have fun. Algot Runeman reminded us periodically how we need to treat ourselves more kindly, and to continue practicing. To allow ourselves to “stumble,” and to measure progress over time.

The point about the importance of play is well-argued in Stuart Brown, MD’s book Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. As he says, “[p]lay is a state of mind, rather than activity” (p. 60). He further states “the impulse to create art is a result of the play impulse… art and culture are something that the brain actively creates because it benefits us…” (p. 60).

Now, I’m off to color.