What is story?

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live…We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” ~ from The White Album, by Joan Didion

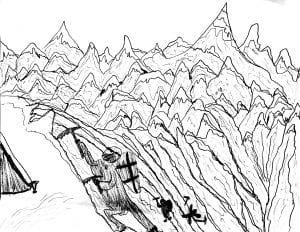

This epigraph is found at the beginning of one chapter in Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air, the book my teenage Meliora students are currently studying. We spent a short time talking about “what is story?” in class, then I asked the students to further explore the question in written essays.

What’s your story by Pixabay shared under a CC0 Creative Commons license.

Their analysis reinforced my belief that young people are very insightful! A few excerpts from their work:

“They [writers] seek to find meaning and then express it in a way that others can read or hear it and nod, to possibly see through that person’s eyes a degree of their view of life.”

“We tell ourselves stories to find the moral lessons in each tragedy, adventure, romance, and every other form of genre.”

“A story is fiction or nonfiction told to entertain.”

“The beautiful thing about stories is that no two people interpret a story in the same way.”

“People can change the world with the stories they tell or the stories they hear.”

“We strive for people to give us advice through books, so we don’t repeat history.”

“There’s always multiple perspectives to every story, and individuals, such as myself, enjoy hearing all perspectives. In the end, this allows you to get a more complete, in depth story.”

“Not everything happens for a reason and that’s okay, sometimes you’re not sure how to understand what is going on in your story or what is going on in the world but take the time to process it.”

“It makes people ask questions and look for answers in their own lives and inspires new generations of passionate storytellers.”